A friend sent me a link to this article last week, which talks about the structure of Japanese horror. It’s quite lengthy but well worth a read. Among other things, it talks about kishōtenketsu – a style of telling stories in four acts, rather than the Western three, without using conflict as the primary plot driver.

At first glance, this really does go against all Western storytelling traditions. Everything we’re taught, and all the media we consume, revolves around creating and resolving conflict. In many ways, it’s how we’re taught to communicate (I’m thinking of debate teams, basically all politics, a good 70% of Twitter, and the badge my mum used to carry on her handbag which said “Because I’m your mother, that’s why”). And certainly the three-act structure is so heavily ingrained that we barely recognise something as a story if it doesn’t follow that pattern. So how does kishōtenketsu work, and how well does it translate to Western audiences?

The Extra Act

We’re used to story patterns that look like this:

Where the action rises due to conflict, which comes to a head, and is then resolved

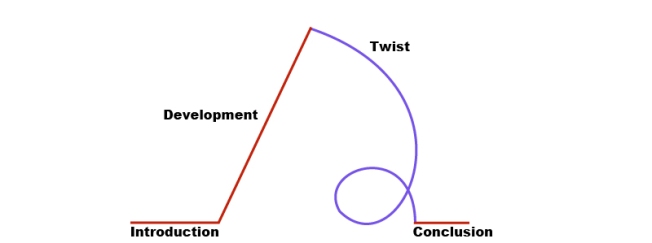

The Japanese approach looks like this:

The extra act, then, is the Twist. In this context, it’s essentially a chance in perspective which makes you reevaluate the events that have preceded it and thus creates tension. It’s best illustrated in horror, with stories like The Licked Hand:

- Introduction (ki): A young girl is home alone with only her pet dog for comfort.

- Development (shō): She hears on the news of an escaped convict and becomes frightened. She is too scared to go to sleep without letting the dog lick her hand from beneath her bed.

- Twist (ten): When she awakes she discovers that her dog is dead and has been the entire night.

- Conclusion (ketsu): She finds the words “HUMANS CAN LICK TOO” written in blood.

There’s no direct conflict in the story, no goal or motivation, and very little action. The entire tension of the story comes from realising that what you thought happened is not what actually happened.

Causality, rather than conflict, is the vehicle in this type of storytelling. ~ Rudy Barrett

This approach is common across multiple genres in Japanese writing. The scholar Utako Matsuyama attributes it to a fundamental difference in cultural attitude. Unlike the goal-driven capitalism of the West, traditional Buddhist values in Japan focus on eliminating worldly desires. That tends to leave protagonists without a goal – and therefore without opposition to it – which necessarily changes the way stories are told. Conflict is replaced with shifting perceptions of the world. Characters aren’t driven or called to action – things just happen to them. And there’s often no resolution, as we would understand it, but instead just an emphasis of the idea or moral shown in the story.

Same, Same, But Different?

It’s this last point that makes the cultural crossover most challenging. We demand a lot from our endings – a satisfying fate for all concerned, neatly tying up every sub-plot, providing a sense of closure and impact – and if they fail to deliver we judge the entire story by that failure.

Twists, however, are very familiar to Western stories. They’re a staple of our psychological horror genre and a common technique employed by unreliable narrators. They go in and out of style a bit, but we always enjoy a good one and it seriously increases the memorability of a story. We like to be conned, provided it’s done well.

Signs let me down, it let Joaquin Phoenix down, but most of all it let itself down.

There’s also a number of people who’ve written articles about how conflict is purely a matter of perspective. I read one example (which I now can’t find again, sorry) which framed the story of Star Wars: A New Hope as a kishōtenketsu by focusing on Han Solo’s character development rather than the intergalactic struggle for dominance. Another, unrelated, gave an example of a kishōtenketsu as a fisherman going out to sea (1), catching his dinner (2), his wife and kids hiding from bandits at home (3), and them all being reunited (4). I’d argue that hiding from bandits automatically implies conflict. With the example of The Licked Hand above, again the presence of an escaped convict writing in blood strongly suggests conflict (or at the very least, its looming potential). So there seems to be some fuzziness on the definition of the presence of conflict. Is the hovering possibility of conflict distant enough from the page to count? In which case, I’d argue that Bronte’s Jane Eyre fits fairly neatly into the kishōtenketsu structure:

- Jane leaves Lowood School to work for Mr. Rochester of Thornfield Hall.

- Jane falls in love with Mr. Rochester but discovers he has a wife.

- Jane runs away and inherits a fortune from a (very) distant relative, whilst Thornfield burns down in her absence.

- Jane and Mr. Rochester are reunited, with both wife and class distinctions removed.

Compare this with a 3 Act structure breakdown:

- Jane leaves Lowood School to work for Mr. Rochester of Thornfield Hall, with whom she falls in love.

- Jane discovers Mr. Rochester has a wife and runs away.

- Jane inherits a fortune and returns to a conveniently widowed Mr. Rochester.

Same story, right? Same amount of conflict, just viewing things from a slightly different perspective.

Which, I think, is actually the point in the end. You can tell the same story from multiple angles, simply by deciding what to focus on. The question is what do you, as the writer, think are the important aspects of your story? And remember – it doesn’t have to be conflict. Whatever ‘conflict’ means.

I’m going to start my write-up of Nine Worlds with the presentation I made, purely because a number of people asked for a copy of my slides and I promised to put them up here. The subject was ‘Choosing your narrative technique in order to have the desired impact on your audience’. I deliberately used the word ‘audience’ rather than ‘reader’ as it’s more applicable across different media (although I forgot to take games into much account, for which I must offer particular apologies to

I’m going to start my write-up of Nine Worlds with the presentation I made, purely because a number of people asked for a copy of my slides and I promised to put them up here. The subject was ‘Choosing your narrative technique in order to have the desired impact on your audience’. I deliberately used the word ‘audience’ rather than ‘reader’ as it’s more applicable across different media (although I forgot to take games into much account, for which I must offer particular apologies to

Also called folk-mythological time. Basically, the world splits into folklore/myth and history. Myth happens Before, and is generally unquantifiable. If you can stick a date on it, it’s history. Importantly, mythological time generally Before but Here. The events of mythological time happened on home ground rather than abroad but, because it’s Before, that home ground is slightly alien – without being foreign. Mythological time is a way of invoking that very specific ‘familiar but different’ feeling that using

Also called folk-mythological time. Basically, the world splits into folklore/myth and history. Myth happens Before, and is generally unquantifiable. If you can stick a date on it, it’s history. Importantly, mythological time generally Before but Here. The events of mythological time happened on home ground rather than abroad but, because it’s Before, that home ground is slightly alien – without being foreign. Mythological time is a way of invoking that very specific ‘familiar but different’ feeling that using