If you’re writing the kind of story where spacecraft are a central feature then you probably want to put some thought into their design. But even if they’re just serving as a location or backdrop, you can jar your readers’ immersion with a spaceship that contradicts their expectations too badly.

Space travel in science fiction often draws parallels with the sea; fictional spacecraft often feel a lot like ships; to the point where that’s entered the popular consciousness. We’ll talk about some of the aspects naval architects consider when designing oceangoing ships, and how you can use them to invent spaceships that feel like they match the feel of your setting.

Speaker: Dr. Nick Bradbeer

This talk was given by my dear friend Dr. Nick, who was a little concerned that there wouldn’t be much of an audience as it was the first session on Sunday morning after the late-night disco. There was, of course, standing room only. Silly Dr. Nick. 🙂

Is Space An Ocean?

The developing design of spaceships in fiction can be directly linked to our changing perspective of space. We originally thought of space as being basically a bit like air, and all the spaceships looked a little like planes or rockets. That changed in the 60s with the advent of Star Trek (correlation, probably not causation), when we started to think of space as more equivalent to water. (Disclaimer: this is purely in literary terms. The scientists continued to be factual about it.) That shift in thinking fundamentally changed the way we talk about spaceships in our stories. For a start, they became ships. They gained large crews, decks, command centres on the bridge, and cannons. Laser cannons, sure, but still.

From this…

… to this

This was, I think, the underlying point of the talk. Spaceships of the kind we write about in SFF aren’t possible – at least, not yet – so you as the writer get to decide the medium you’re designing them for. You build your own rules, however close to actual physics they end up being, and follow them.

Designing Your Rules

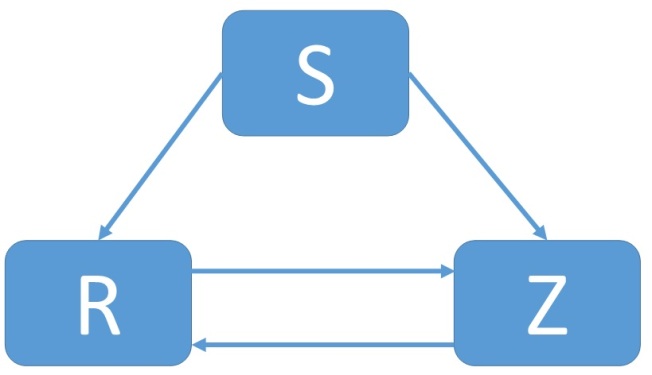

Technology has four distinct phases, and you need to decide which phase your spaceships are in:

- Experimental: ridiculously expensive. The world can afford to build one of these. (e.g. International Space Station)

- Governmental: very expensive, affordable only by governments and mega-corporations. (e.g. space programmes)

- Commercial: expensive, but within the price range of most corporations. (e.g. planes)

- Personal: affordable by the average individual. (e.g. cars)

Your setting should have some form of technology at every phase of development, otherwise the setting won’t feel developed or developing.

You also need to consider the Mohs Scale of SciFi Hardness. How far do you want to bend physics? If you’re ignoring real physics, it’s still good to have consistent rules of fake-physics within which your technology operates. (Otherwise, just call it magic and be done with it.) Dr. Nick is a fan of the One Big Lie approach, wherein most physics is normal but one law is breakable or one piece of technology is impossible, such as the FTL (Faster Than Light) drive which makes it actually possible to travel between star systems.

Physics, schmysics

Form & Function

Generally speaking, the more mature your technology, the more aesthetic freedom you have in design. When the tech is experimental, the aesthetic tends to be quite function-driven and practical. As it moves towards the personal, freedom of design creeps in. There’s also a correlation in Sci Fi between aesthetic freedom and soft science: the less applicable real-world physics is to the setting, the more freeform the spaceship design tends to be.

There are, however, several aspects of function which will impact design:

- Role: what is the payload and performance of the ship? Does it need to be fast, durable, stealthy, carry cargo, carry crew, etc? Is it offensive or defensive? Does it carry smaller fighters? (More on that below.)

- Sizing: this is the balance of weight, space and power. Again, more on this below.

- Layout: does it take off vertically or laterally? Are there lots of internal subdivisions (the ability to compartmentalize air is often useful)? Does it need to be cramped into as little space as possible, or is this completely irrelevant (like Star Wars Star Destroyers)? Do you want to separate your living areas from your engine areas, or not? What is the traffic flow of people like?

A note on fighter carriers: these only work if the fighters are actually useful, otherwise you’re putting a lot of resources into something unnecessary. Fighters are useful if they carry out a function the carrier can’t, like operating in a different element such as a carrier ship with fighter planes. In space that isn’t applicable, so the fighters need to have a different difference to the real world. For example, as long-range scouts if the technology for scanners is only short-range, or for torpedo delivery if weapon tech is at a level where torpedoes are a sensible battle option.

Magic tech: where form and function completely ignore each other

Size Does Matter

When working out the balance between weight, space and power, there are certain weight groups that need to be considered. These include structure, drives, personnel, power and heat, and payload.

Structure refers to both the external hull and the internal integrity. Is it shaped like a ship or a rocket? Does it need reinforcing ribs internally? Ribs make things look solid – they’re often used in spaceship design where they aren’t strictly needed because it’s such a strong aesthetic.

Drives refers to the method and speed of propulsion. Does your ship have a small thrust and build up speed slowly (microthrust), or lots of thrust which builds up speed very quickly but is far more fuel-intensive and potentially painful for your crew (torch ship)? The speed of travel is really important for your wider setting – it impacts politics, interplanetary communications, warfare, cultural spread, and a host of other things. In the RPG Traveller, for example, radio waves can’t travel any faster than ships, so everything works in the same way as it did in Earth’s Age of Sail. Ships are relied on to carry messages, and no communication can outrun the fastest ship.

Personnel refers to the number of crew on a ship and therefore the amount of space they take up. Technology miniaturizes but people don’t. They need places to eat, sleep, wash, exercise and breathe (yay, life support). They also need to be shielded from the radiation typically found in space.

Power and heat refers to the amount of heat given off by the engines and various other systems, which will vary depending on the ship’s function. Venting heat into space is super-important if you don’t want your ship to explode, so external radiators are an important and often-overlooked feature.

Payload refers to the weaponry. Does it need fuel of some kind? Does it need ammunition? Does it need recoil space? How big is it, how many people are required to operate it, what is the range capability?

Defying Gravity

How are you creating artificial gravity? It isn’t something you can just turn on with the flick of a switch – it depends on your ship’s drives and style of propulsion. If you have low-thrust drives, they will only create a weak gravity. If you have really high-thrust drives, they run the risk of flattening your crew.

Most sci fi ships create gravity by spinning in some way. Either the whole ship spins on it’s lateral axis (or, more excitingly, the vertical one, known as the Tumbling Pigeon), or the habitation part of it does in a ring or compartments around the ship’s core. If none of your ship spins at all, the creation of artificial gravity might be the One Big Lie in your setting.

And Finally, Air Ships

Ships are dense. Air is not. It requires a LOT of air to lift a very very small, very very light ship. Get the proportions right. The airships in the 2011 Three Musketeers movie need not apply.

Dr. Nick has kindly shared his slides here, and is on Twitter here.

Next week: how to horrify your audience.