It’s been a while… half a year, in fact. Apologies for the radio silence. Uni has been almost entirely focused on writing my book so I’ve had very little non-book related stuff to share and even less time to do it in. But things are starting to move over the summer, so it’s time to get back on the horse. 🙂

The Evolution of the Novel

I was pointed towards the essays on The Dialogic Imagination by Mikhail Bakhtin by my tutor recently. Bakhtin was a Russian philosopher and literary critic writing in the early 1900s, and he had some interesting ideas about the novel as a genre. Until now I’d assumed that the novel was a format, and things like horror, romance, SFF, etc were genres which used that format. Not according to Bakhtin. He classes the novel as its own genre, separate to the epic, the elegy, the lyric poem, and all the rest of the classical literary styles. These styles were rigid, with strict formats and defined subject matter. The novel is much more fluid, defying categorization because there’s always multiple exceptions to any rule you try to impose. It essentially bastardized the subject matter of the older genres, turning it on its head:

The “absolute past” of gods, demigods and heroes… is brought low, represented on a plane with contemporary life, in an everyday environment, in the low language of contemporaneity. ~ Epic and Novel, Bakhtin

This did something important. The older styles were very much for the elite – the educated upper classes. Within their stories, the world might change on a cosmic scale (the end of the Age of Heroes in The Iliad, for example) but not on a day-to-day level. This is because the intended audiences were the people in charge, and they had no interest in social change. The novel messed with that. It began the move from elite audiences to everyman audiences, bringing the subjects within reach of the general public. And the general public were very interested in social change, oh yes.

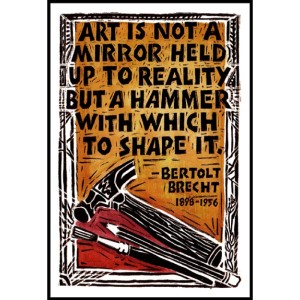

The novel was a way to push boundaries, to discuss the issues of the day in a relatively safe medium. And, because it was so flexible, it could incorporate all the favourite subjects of the old genres – such as love, war, death and heroes – without breaking a sweat. It took over from the old genres, in fact, because it could cover those subjects with greater freedom and exploration.

…the unfettered and fantastic plots and situations all serve one goal – to put to the test and to expose ideas and ideologues. ~ Epic and Novel, Bakhtin

The rise of the novel also meant a shift in focus. The epics and elegies were focused on the past; lyrical poetry was, at best, focused on the present. The novel allowed speculation about the future. How things could change. It was the genre of evolution.

Genres Today

The novel is now such a ubiquitous format that we don’t think of it as a genre. We sub-divide it into themes or subject matter or style, and call them genres instead. Some of them still talk about contemporary issues and push boundaries; others are purely for entertainment’s sake, and there is nothing whatsoever wrong with that.

I think, though, that SFF has an important role to play in pushing boundaries. As I’m pretty sure I’ve mentioned before, it’s a step back from the world which means we can talk about problematic areas like religion and race without falling foul of prejudices or sensibilities. It’s also a way to discuss social problems in a very bold way, with less risk (I’m going to point you back to the lecture on Chinese SFF from last year). And it is, absolutely, the genre of the everyman audience.

Urban fantasy, which is what I’m currently writing, straddles the line between reality and fantasy. It makes this balance of open discussion vs removed engagement a little trickier, but it also allows us to make more pointed observations. Urban fantasy isn’t new, incidentally – it has its roots in the gothic novel. Arthur Machen, Mary Shelley, Edgar Allen Poe, they were all forerunners in the fantastical. And they were all making observations about the society they lived in.

Urban fantasy, which is what I’m currently writing, straddles the line between reality and fantasy. It makes this balance of open discussion vs removed engagement a little trickier, but it also allows us to make more pointed observations. Urban fantasy isn’t new, incidentally – it has its roots in the gothic novel. Arthur Machen, Mary Shelley, Edgar Allen Poe, they were all forerunners in the fantastical. And they were all making observations about the society they lived in.

I’ve had to define the issues I’m deliberately trying to tackle in London Under, and to be honest they aren’t what I thought they would be. I thought I was writing about love and duty, and what those forces can do to us when they’re in opposition. It turns out that, rather without meaning to, what I’m actually writing is a story about the threat of terrorism and the fear of loneliness in a big city. The whole ‘love and duty’ thing is still there, but more as an undercurrent. I didn’t plan that, it just seems to have happened. Which shows that your subconscious can sometimes be the better writer.

Our era is characterized by an extraordinary complexity and a deepening in our perception of the world; there is an unusual growth in demands on human discernment, on mature objectivity and the critical faculty. ~ Epic and Novel, Bakhtin