Last weekend was Gollancz’s annual Literary Festival, celebrating all things SF&F. For the first time I splashed out on a ticket and went along to a couple of panels by such giants as Joanne Harris, Joe Hill, Alastair Reynolds, Aliette de Boudard, Adam Ross and Pat Cadigan. From them, I learned three important lessons:

- Joanne Harris is exactly as much of a geek as I always hoped she’d be.

- Pat Cadigan’s comic timing is absolutely perfect.

- They are people just like me, with the same writing challenges and struggles. If they can do it, so can I.

That said, there were a few pearls of more specific wisdom that came out of the panels. I’ll do my best to assemble them into a coherent post, but the conversations veered quite abruptly so there may be some jumping around.

Publishing & Medium

Harris: You have to be rejected. You have to be rubbish for a while before you’re good. None of your time spent writing is ever wasted. It’s all experience that gets you to the next level. Self publishing is a great option which I’m glad I didn’t have.

Hill: With self-publishing, the readers have become the gatekeepers. They will tell you if you’re any good in the Amazon reviews. But your crappy stuff will still be out there.

Cadigan: Editors are your best friends. They stop you going out with spinach between your teeth. I woke up one morning knowing how to turn my current project into a trilogy, and I had to take a tranquilliser.

Harris: JK Rowling, Philip Pullman, Lemony Snickett – they were all game changers in publishing trends. Before them, lots of rejections were based on the belief that such books were too adult for kids and too childish for adults.

Hill: In the 19th Century illustration was understood to be part of the publishing package. Illustrations perfectly captured the character on the page. When Modernism came along, illustrations became viewed as for kids, or very middle class and not high art with a plot. So illustration fell by the wayside. Now so much of our media is digital so it’s great to use it to enrich the analogue page. Illustrations are poised to come back.

Harris: As soon as you send the book out to the public, you’ve released control. That’s how it should be. Everyone will take out of a book what they need, and it’s not necessarily what you put in there but that’s good.

Even when all of us speak the same language, none of us speak the same language.

Harris: I write stories live on Twitter and see how the audience responds as we go. It forces you to think differently about structure, both overall and at a sentence level. Every sentence has to be formed in a different way. A story on the page is different to a story read aloud.

Writing Emotionally

Harris: ‘Write what you know’ is rubbish. There’d be no fantasy, and all crime writers would be in jail, if we did that. But it has to be emotionally true to you. Don’t write love if you’ve never been in love.

Hill: Find a writer you love and try writing them. Go through a page and work out why they did stuff. Can you do it differently? Can you do it better? Write dialogue trees – just dialogue alone, no descriptions or directions. It helps clarify the voices of different characters.

I want to know how a guy dresses from the way he talks. – Steinbeck

Harris: I give my characters D&D stats – Intelligence, Charisma and Constitution. It makes you think of them differently. How are they able to react to different situations, if they have low Cha or low Con? You need to know everything about them, even if you don’t put it on the page. How would they answer internet memes? Or choose from a menu? Go for a walk as your character – what would they notice? Stanislavski’s Method Acting books are my most valuable writing resource.

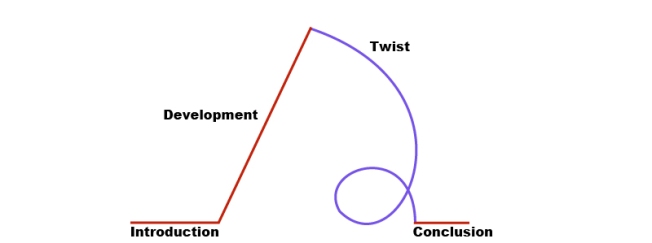

Planning & Plotting

Ross: If I plan in too much detail, it becomes a chore to write the book and boredom communicates to the reader. First you get it written, then you get it right.

Cadigan: You’re always a bit smarter than you think you are, and you know more about human behaviour than you think you do. Leave enough wiggle room to let that happen.

Reynolds: I always have a skeleton as a reference point, to navigate back from a tangent, but generally I like to be surprised. The downside is you end up throwing a lot of material away.

Cadigan: The dishes are in the sink but I’m too lazy to wash them, so I might as well write a book.

Thank you, Pat, for that inspiring call to action!